How will the removal of the Code for Sustainable Homes affect the implementation of future sustainable housing? What will this mean for the subsequent transition period?

The news in 2014 was awash with articles regarding the housing crisis and the consequent shortfall in the number of new homes being built. In the case of London this deficiency is particularly pertinent, where the GLA target for supply is estimated to fall 14,400 homes short of demand. The Housing Standards Review aims to unravel and simplify the current framework and therefore speed up the house building process.

Over the following paragraphs, we will take you through some of the big issues around the withdrawal of Code and the transition period to the New Building Regulations Approved Documents, as recognised by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) and BRE amongst others.

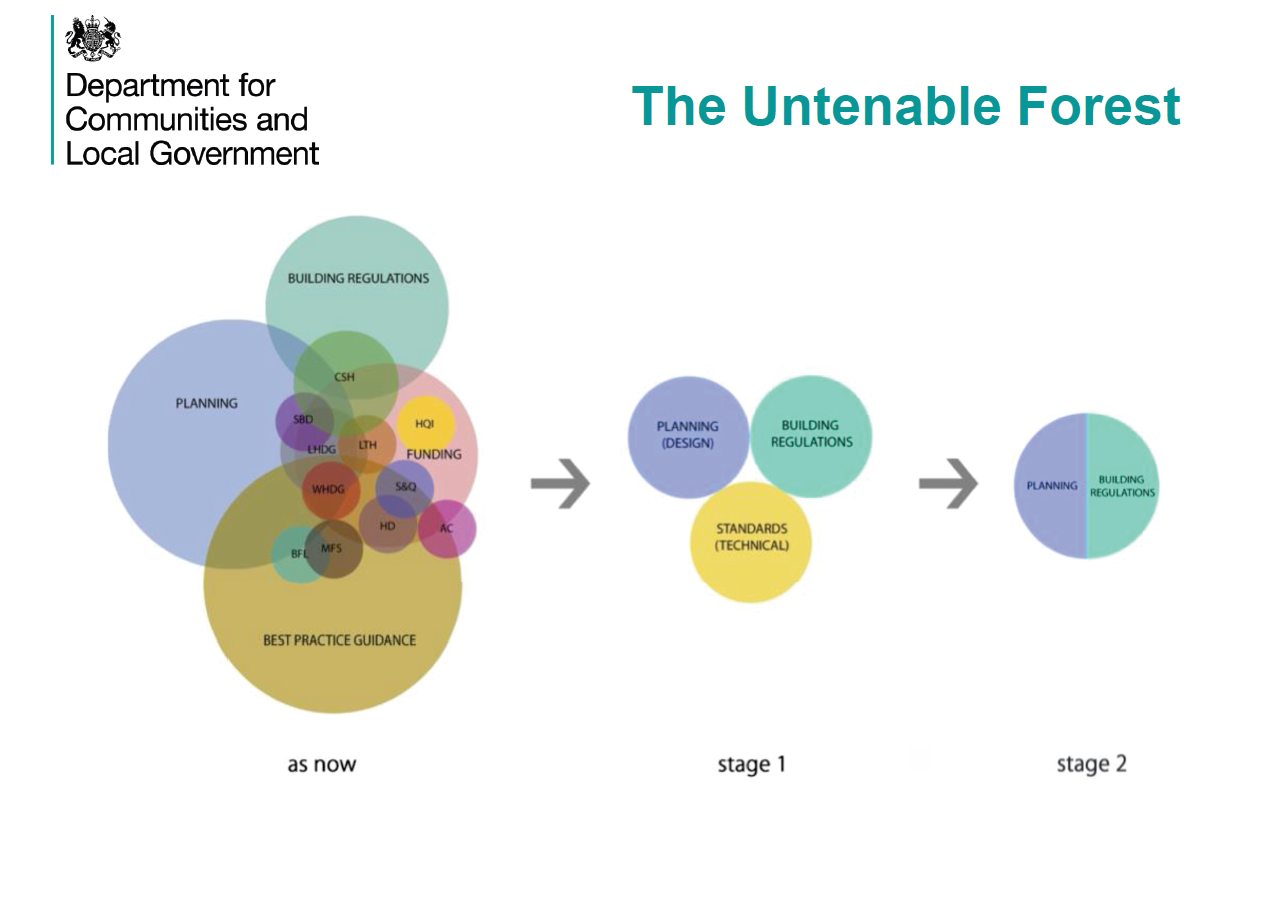

The current framework – as shown on the left hand side of the image below – is a jumbled up mix of overlapping and contradicting policies and regulations. The Housing Standards Review seeks to resolve this through the implementation of the subsequent Stage 1 and Stage 2 (New Approved Documents) standards. These will attempt to: reduce bureaucracy and costs, reform and simplify the framework, make the housebuilding process easier to navigate, reduce contradictions and overlap, and allow local choice but within sensible parameters. Part of this reform includes the Withdrawal of the Code and the stripping of Local Authority’s (LA) power in enforcing many sustainability targets.

The DCLG has laid out a timeline of how it intends to phase out the Code and transition to the New Approved Documents, with the three important dates being:

- Spring 2015: The new regulations are likely to be introduced in form of a planning statement. After issue of this statement, The Code is wound down and Local Authorities (LAs) will no longer be able to enforce specific sustainability and energy requirements for planning

- October 2015: The New Approved Documents will kick in, incorporating part of the Code as mandatory standards, and additional parts as optional standards. LAs can then select and consolidate the optional standards that they would like to implement as planning requirements

- October 2016: The new planning and energy act will commence to target zero carbon for all developments

As you can see this will leave a significant gap in time between when the new regulations are announced and when they actually kick in. There was a lot of confusion as to what the sustainability and energy standards would be during this window; the DCLG is undoubtedly keen to accelerate the housebuilding process and is perhaps aware that this ambiguity averts attention from them for the time being. It is likely that there will be a boom in the number of accepted planning applications for new homes over the summer, but at what cost to the environment and the occupier?

As it stands, there are only five sustainability categories that will be carried over from the current regulations into the New Approved Documents standards. These are:

- Energy – Homes will have to meet the baseline regulations (Part L 2013 update) only but will have to be Zero carbon from 2016. LA’s may have the power to request for Code Level 4 energy requirements (19% reduction) up until 2016.

- Water – Baseline regulations (Part G) will have to be met. Potential for a higher standard (105lpd). These standards may vary depending on the location.

- Access – Baseline regulation (Part M) will remain with 2 additional areas (equivalent to Lifetime Homes, and wheelchair housing).

- Security – A single minimum level of Secured by Design will be proposed.

- Space – Consolidating the current regulations into one ‘nationally described standard’

At the moment there are no other regulations or standards proposed, which means that all of the current sustainability criteria upheld by the Code and other LA requirements – such as ecology, material use and flood risk – will be removed. The exclusion of side wide criteria illustrates the government’s perspective that the built environment is absolved from responsibility for wider sustainability issues. Given recent issues such as rapidly declining biodiversity and the flooding in West London, this is difficult to comprehend. The lack of influence held by the LAs to enforce sustainability criteria that is influential on a borough scale is also slightly worrying. (Not to mention the disturbance to neighbours that may be caused during construction and operation).

It is likely that Building Control will be responsible for ensuring sustainability measures are implemented on site, rather than the Code assessors, as part of their post construction site inspection which will be difficult to for a department that is stretched as it is.

The BRE is currently developing a new domestic standard, but it will be a voluntary standard and will not be enforceable by LAs. The aim is to focus on build quality and quality of homes, and shall be driven by both the client and the occupants. There is no clear indication on what the Domestic Standards would include – they will be launching their scheme in Ecobuild 2015 – so we may have to wait until next week to find out. ‘Quality’ of housing was a point that is regularly touched upon; the DCLG and BRE seem assured that build quality will continue to be driven by both the client and occupants. This is questionable, given the overwhelming difference between demand and supply of new homes, and the upcoming absence of sufficient regulation.

While it is hard to argue that the current assortment of criss-crossing regulations are a little illogical, the removal of CfSH and the lack of clear energy and sustainability targets for domestic developments to fill the void is a big step backwards. Particularly in London where it has been proven that is it technically and financially feasible to achieve Code Level 4 and a 35% regulated CO2 reduction across majority of the new-build developments within the Greater London area. There will be developers and housing associations that are willing to take up the voluntary BREEAM Domestic standard, however, the low cost mass market developer is unlikely to voluntarily opt for the standard if there is no regulation to enforce its implementation – this could potentially flood the market with poorly constructed, inefficient and unsustainable housing that the Local Authorities will have no control over.

Perhaps a single word used by the DCLG best sums up the government’s current standpoint on sustainability in the built environment. They state that the new regulations will allow Local Authority choice but within ‘sensible’parameters, demonstrating that they still view sustainability as a luxury, and not a necessity.